Troubleshooting Neutron networking

Neutron is a bit of a special case among the OpenStack components because it relies on and manages a fairly intricate collection of transport resources. These may be created as a result of Neutron resources being defined by end users. There is not always a straightforward correlation at first sight. Let's walk through the traffic flow for an instance to make sure that you know which agent is doing what within the Neutron infrastructure.

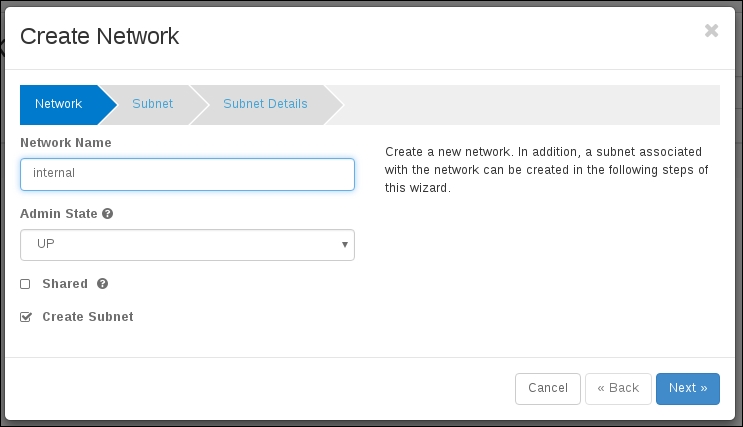

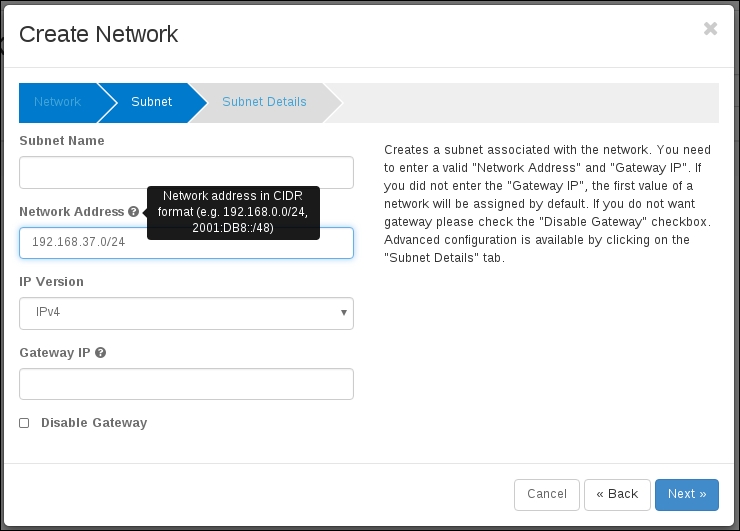

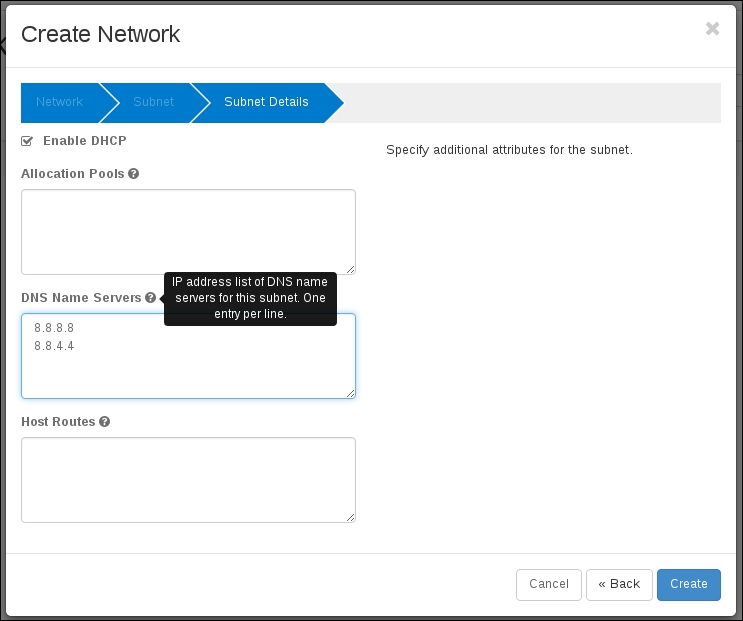

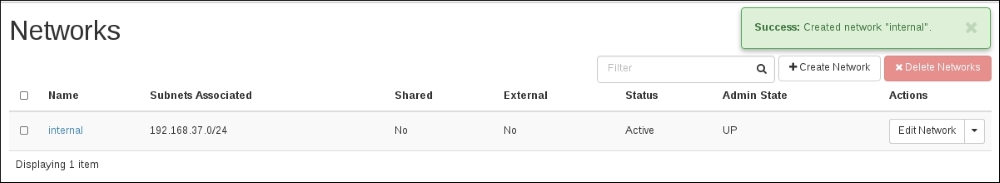

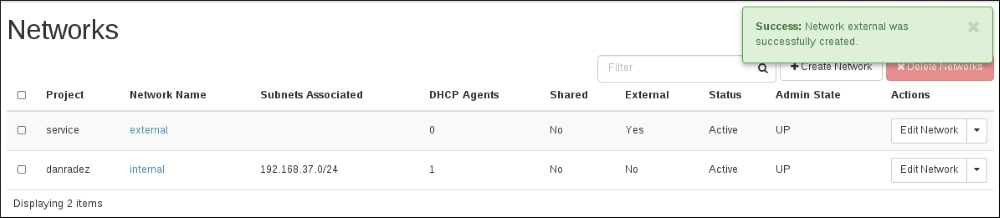

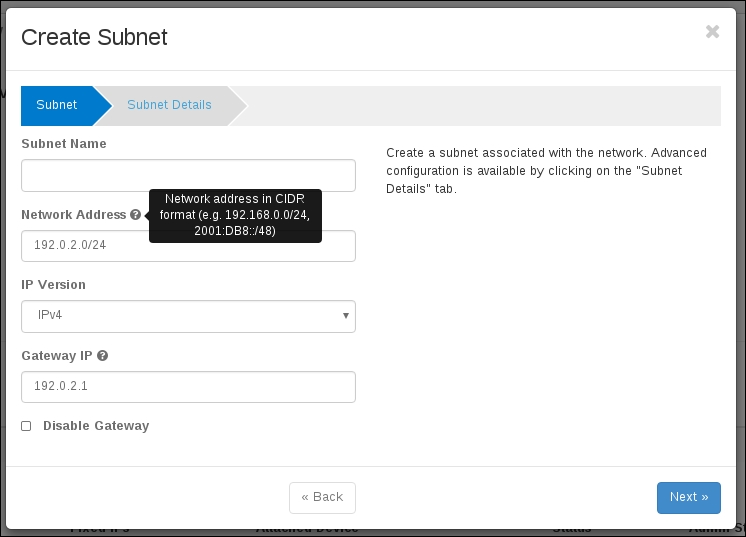

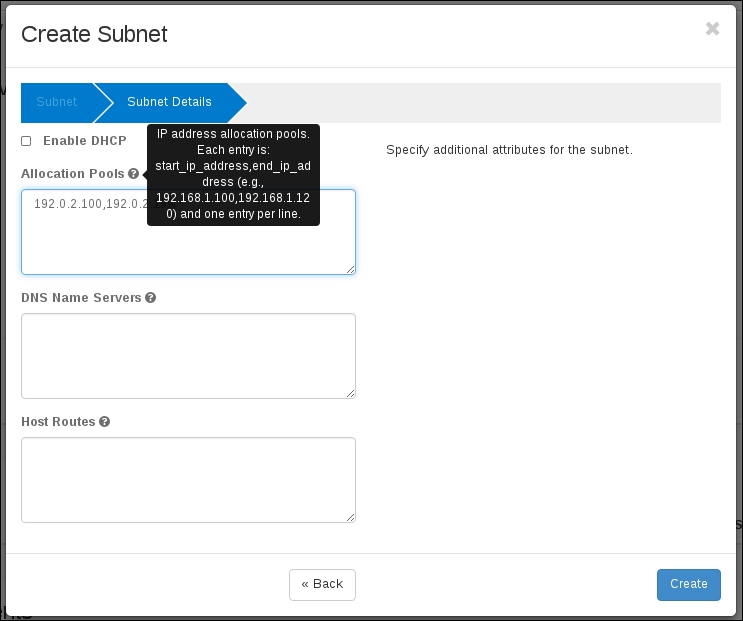

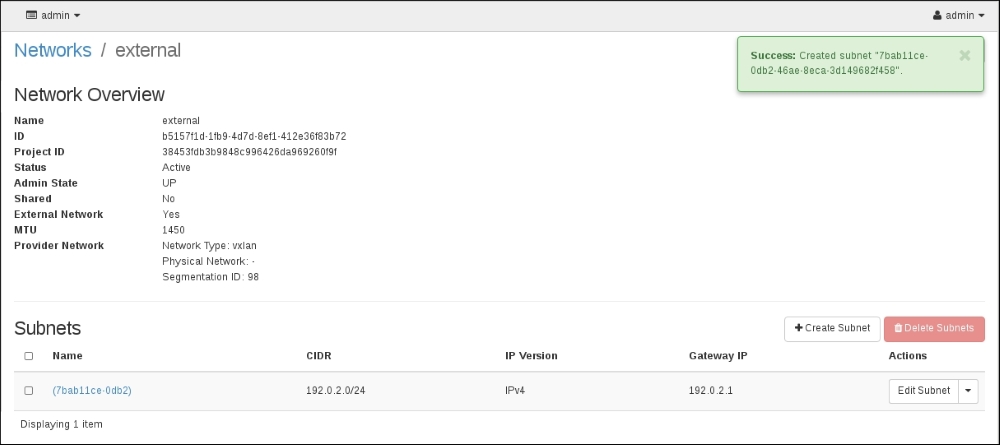

The first thing that an end user will do before launching an instance is create a network specific to their tenant for their instances to attach to. At the system level, this translates into a network namespace being created on the node that is running the Neutron DHCP agent. Network namespaces are virtual network spaces that are isolated from the host-level networking. This is how Neutron is able to do isolated networks per tenant. They all get their own network namespace. You can list the network namespaces on any Linux host that has network namespaces enabled, using the ip utils command:

When you run this command, if you have some networks already defined, you see namespaces named qdhcp-{network-id}.

Note

The letter Q is a legacy naming convention from the original name Neutron had, which started with the letter Q. The old name had a legal conflict, and it had to be changed.

So a qdhcp network namespace is a namespace created to house the DHCP instance for a private network in Neutron. The namespaces can be interacted with and managed by the same tools as the host's networking by just indicating the namespace that you want to execute commands in. For example, let's list the interfaces and routes on the host and then in a network namespace. Start with the host you're on. The following command shows this:

The interfaces listed should be familiar, and the routes should match the networks you are communicating with. These are the interfaces and routes that the host that OpenStack is installed on is using. Next, get the ID of the network you would like to debug, and list the interfaces and routes in the namespace using the netns exec command. This is shown by the following command:

The same commands are executed inside the namespace and the results are different. You should see the loopback device, the DHCP agent's interface, and the routes that match the subnet you created for your network. Any other command can also be executed in just the same manner. Get the IP address of an instance of the tenant network and ping it:

There is even an independent iptables rule space in this namespace:

The ping is important because by pinging the instance that is running on the compute node from the qdhcp network namespace, you are passing traffic over the OVS tunnel from the network node to the compute node. OpenStack can appear to be completely functional – instances launch and get assigned IP addresses – but then the tunnels that carry the tenant traffic aren't operating correctly, and the instances are unreachable by way of their floating IP addresses.

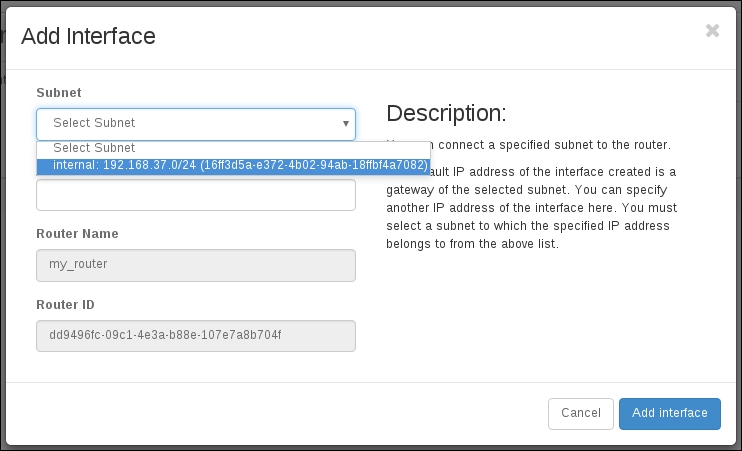

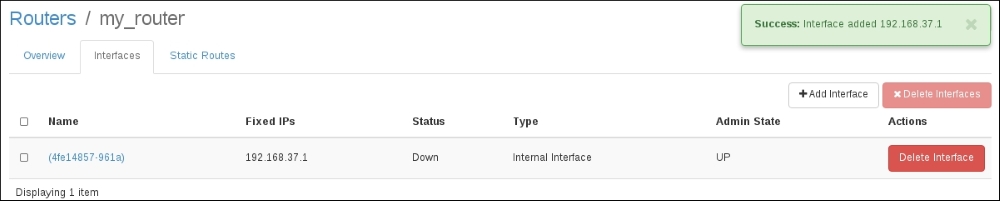

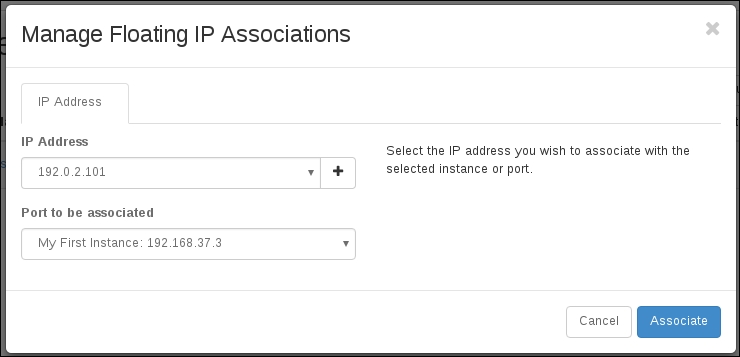

To debug an unreachable host, you have to traverse more than one namespace. The qdhcp namespace we just looked at is one of the namespaces that an instance needs to communicate with the outside world; the other is the qrouter. The OpenStack router that the instance is connected to is represented by a namespace, and the namespace is named qrouter-{router-id}. If you look at the interfaces in the qrouter, you will see an interface with the IP address that was assigned to the router when the tenant network was added to the router. You will also see the floating IP added to an interface in the qrouter.

What we are working towards is tracing the traffic from the Internet through the OpenStack infrastructure to the instance. By knowing this path, you can ping and tcpdump to figure out what in the infrastructure is not wired correctly. Before we trace this, let's look at one more command:

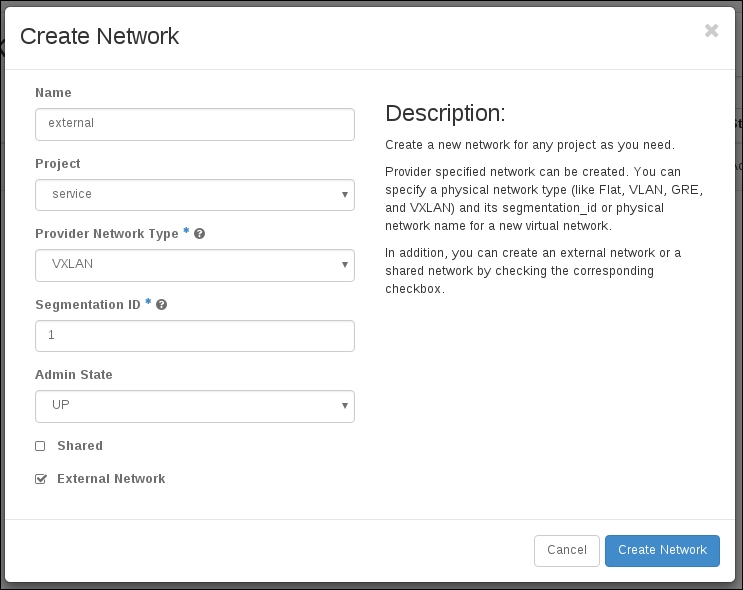

This command will list the bridges and ports that Open vSwitch has configured in it. There are a couple of them that are important for you to know about. Think of a bridge in OVS as somewhat analogous to a physical switch, and a port in OVS is just a network port on a switch or a physical port on a physical switch. So br-int, br-tun, br-ex, and any others that are listed are virtual switches and each of them has ports. Looking at br-int first, we can figure out that this is the name of the bridge that all local traffic will be connected to. Next, br-tun is the bridge that will have the tunnel ports on. Not all hosts will need to use br-ex; this is the bridge that should be connected to a physical interface on the host to allow external traffic to reach OVS. Finally, only in the case of a VLAN setup is there a custom bridge setup. We are not going to look at them in this book, but you should know that the three we are discussing are not the exclusive list of OVS bridges that OpenStack uses. The last thing to note here is that some of these bridges have ports to each other. This is just like connecting two physical switches to each other.

Now, let's map out the path that a packet will take to get from the Internet to a running instance. The packet will be sent to the floating IP from somewhere on the Internet. It should go through the physical interface, which should be a port on br-ex. The floating IP will have an interface on br-ex. The virtual router will have an interface on br-ex and br-int and will have iptables rules to forward traffic from the floating IP address to the private IP address of the instance. For the packet to get from the router to the instance, it will travel over br-int to br-tun, which are patched to each other, over the VXLAN tunnel to br-tun on the compute node, which is patched with br-int on the compute node that has the instance's virtual interface attached to it.

With this many different hoops to jump through, there are quite a few places for traffic to get lost. The main entry points for debugging start with namespaces. Start by trying to ping the instance or the DHCP server for the tenant in the namespaces and move to tcpdump if you need to. Pings and tcpdumps can be a quick diagnosis of where traffic is not flowing. Try these tests to track down where things are failing:

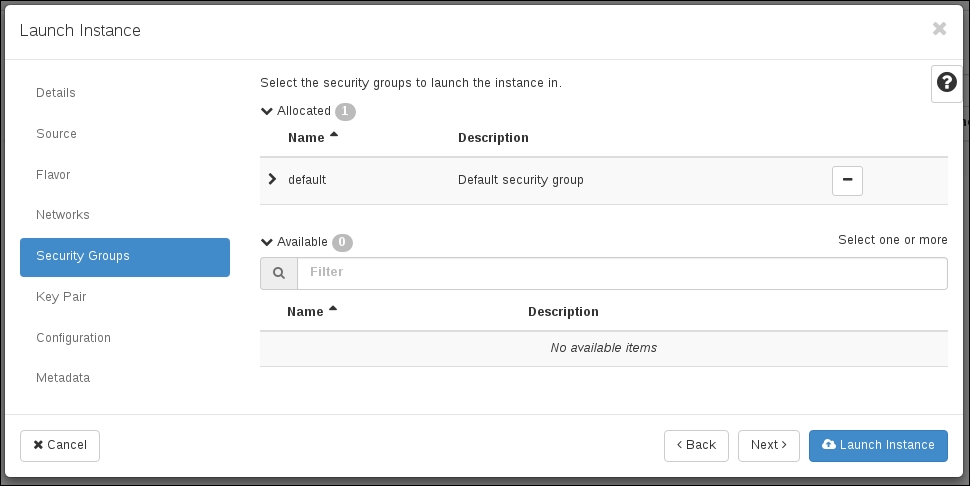

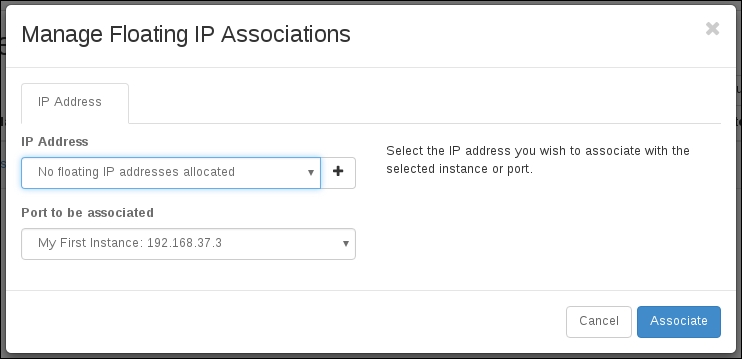

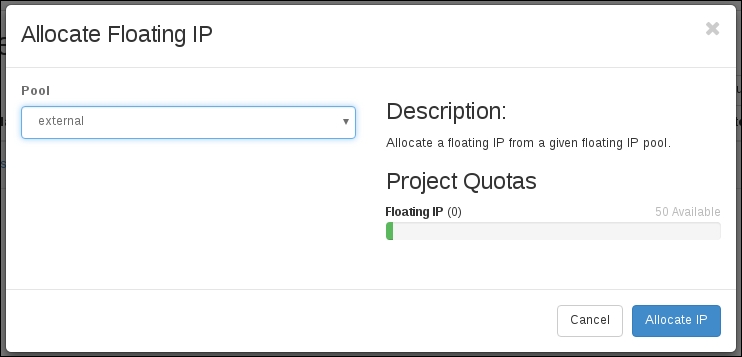

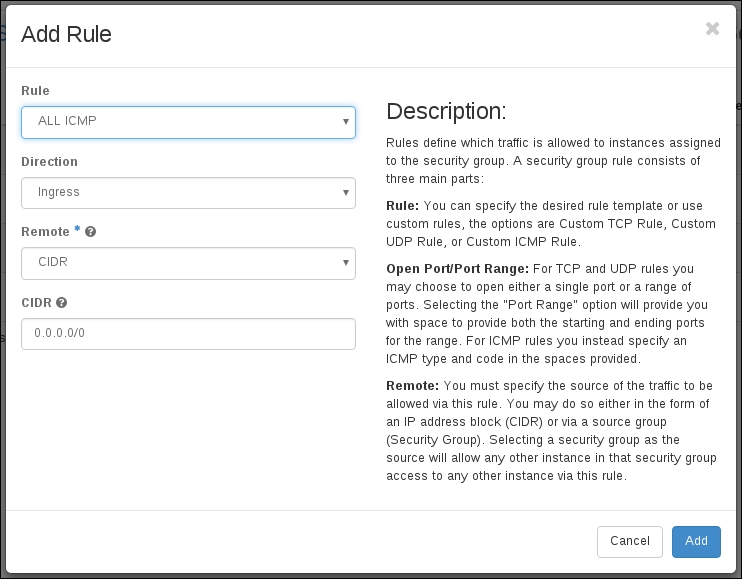

Make sure that ICMP is allowed for all IP addresses in the security groups

Ping the instance from the qdhcp namespace

Ping the instance from the qrouter namespace

Tcpdump ICMP traffic on physical interfaces, br-int, br-tun, and br-ex as needed

These pings establish first that traffic is flowing over the VXLAN tunnels and that the instance has successfully used DHCP. Secondly, they establish that the router's namespace was correctly attached to the qdhcp namespace. If the ping from qdhcp doesn't succeed, use ovs-vsctl show to verify that the tunnels have been created and check the Open vSwitch and Open vSwitch agent logs on the network and compute node if they haven't. If the tunnels are there and you can't ping the instance, then you need to troubleshoot DHCP. Check /var/log/messages for DHCP messages from the instance on the network node, and boot an instance you can log in from the console to try to dhclient from the instance if you don't see messages from the instance in the logs.

If the initial pings don't succeed, you can use tcpdump on the Open vSwitch bridges to dig a bit deeper. You can specify which interface you want to listen on using the -i switch on tcpdump, and you can drill down to where traffic is failing to flow by attaching to the Open vSwitch bridges one at a time to watch your traffic flow. Search the Internet for tcpdump and ping if you are not familiar with using tcpdump:

Start with br-int on the compute node, and make sure you see the DHCP traffic coming out of the instance onto br-int. If you do not see that traffic, then the instance might not even be trying to use DHCP. Log in to the instance through the console and verify that it has an interface and that dhclient is attempting to contact the DHCP server. Next, use tcpdump on br-int on the network node. If you do not see the DHCP traffic on the network's br-int, then you may need to attach to br-tun on the compute and network nodes to see whether your traffic is making it to and across the VXLAN tunnels. This should help you make sure that the instance can use DHCP, and if it can, then traffic should be flowing properly into the instance from the network node.

Next, you may need to troubleshoot traffic getting from the outside world to the network node. Use tcpdump on br-ex to make sure you see the pings coming from the Internet into the network node. If you see the traffic on br-ex, then you will want to check the iptables rules in the qrouter namespace to make sure that there are forwarding rules that associate the floating IP with the instance. The following command shows this:

In this list of iptables rules, look for the floating IP and the instance's IP address. If you need to, you can use tcpdump in the namespace as well, though it is uncommon to do this. Look up the interface the floating IP is on, and attach to it to listen to the traffic on it:

Using this collection of tests, you should be able to identify where the trouble is. From there, check logs for Open vSwitch and the Neutron Open vSwitch agent for tunneling, the Neutron Open vSwitch agent and Neutron DHCP agent for DHCP issues, and the Neutron L3 agent for floating IP issues.